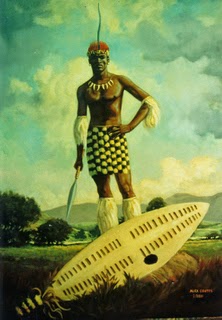

Look

closely at the accompanying painting of King Shaka ka Senzangakhona, twelfth

king of the Zulu nation. The original work was painted several years ago by the

author of this blog, in oils.

|

| King Shaka of the Zulus |

It is a

truthful interpretation, based on forty years of research including the historical

testimony of the trader and friend of the king Henry Francis Fynn. It is arguably

the most accurate representation of the Zulu king anywhere in the world. The

image is offered as a standard for other portrayals. It provides the cover for the

historical novel ‘Shaka, the story of a Zulu king’, found elsewhere on the

website that supports this blog.

The Zulu

king was known for his stature and magnificent physical presence. He projected

dignity and a sense of command, was powerful in build and indeed displayed

‘remarkable athletic ability’ according to the testimony of Isaacs, one of the

traders of his time.

Since

Shaka’s death in 1828, many artists have tried to portray him in paintings or

sculpture. From the often bizarre works seen, one concludes it to be a difficult

task.

The build

should be even more muscular and athletic than most of the earlier attempts,

showing a man whose tall stature was instantly recognizable in a crowd. The posture should be alert, coiled, prepared

for action; for he was a man attuned to the nuances of the times and ready for any

challenge.

Anyone

wishing to do justice to the Zulu king through medium of sculpture would

require a figure at least three metres in height to give the necessary weight

to his presence, while not being banal for its reliance on massive proportions

alone.

King Shaka

was a man of considerable intelligence who planned complex campaigns with great

insight, undertook the training of his irresistible fighting forces with great

skill and managed the integration of numerous lesser tribes and clans into the

growing Zulu nation.

It was a

task requiring considerable gathering and processing of information, logical,

rational, critical and creative thinking, and an acute ability to understand

how social systems work. Engineering the

stabbing spear, designing the battle-formation for attack modeled on the

olden-time hunting tactics of a Zulu family, implementation of complex social

and legal systems, and leadership of the First Fruits and other ceremonies

showed much creative flair.

The manner

in which he overcame the intrigues of rebellious sangomas and the deception

with which he enticed and lured into ambush several invading Ndwandwe hordes

from the northern lands around the Pongola river also reveal his ability to

think divergently. His was a considerable intellect.

There were notable examples of honourable conduct on the king’s part, admiration for bravery and the discharge of duty, forgiveness for those who spoke the truth boldly, and compassion for the poorest amongst the nation. Despite his gravitas, there were glimpses of humour at times. With the later politicization of the king’s record, those who wished to discredit him neatly omitted these attributes while magnifying the harsher side of a harsh reality.

Yet even

the most brutal of the recorded methods of punishment used by the Zulus of the

time were no worse than what was done at the same time in apparently

‘civilized’ nations such as England and France. There, terrible procedures of

hanging, drawing and quartering had been used for more than five hundred years.

In current times, savage and ferocious forms of execution still persist in many

parts of the world.

Any statue

must reflect a penetrating intelligence and the dignity befitting a man of

massive presence and gravitas. He need

not be particularly handsome, since there is no clear record of his features,

yet the sculptor must shy away from portrayals that do not get the features

anatomically in proportion. The face must be absolutely right, and it must be

strong.

For

decoration and a display of power, King Shaka had a band of strung lion’s teeth

encircling his neck. In less formal

attire he wore tassels and even genet skin. He sported a loin covering of

assorted samango monkey, genet and other tails (the isinene) of a length

befitting a senior man, and wore a soft antelope-skin covering (ubeshu) hanging

to behind his knees in his mature years.

His full

headdress was magnificent, being usually bedecked with an apron of red purple-crested

lourie (touraco) feathers inserted in a thick band of leopard skin or brown

otter pelt, all surmounted by a sixty centimetre long blue crane feather at the

front. Around each upper arm and lower leg was a tassel made of long bleached

hair derived from the extremities of cattle tails.

Plugs of

shiny yellow cane were inserted in his ear lobes. The clash and contrast of the

primary colours; blue (the crane feather), red (lourie feathers) and yellow

(cane for the ear decorations) was impressive.

His weapons

consisted of a great white shield taller than most men, made of double-layered

cattle hide with a small black patch the size of the open human hand slightly

offset at the center. It was a blemish to show that even the king did not

regard himself as perfect. The shield

must be that engineered by the Zulu king, and not the smaller version that

crept in during ensuing years under Kings Dingane, Mpande and Cetshwayo.

His spear

was the iklwa! stabbing spear, a metre long with a massive, razor-sharp

hammered-iron blade. The wood was flared at the lower extremity so that it

would be secure in the king’s grasp during battle. It must be displayed in the

right hand, held low since the attacking thrust was upwards under the ribcage,

and not a futile overhand jab.

The image should

preferably show the King in full battle dress, something like the miniature

displayed in the Old Courthouse Museum in Durban. He might be leaning slightly forward, or at

least be balanced to show a powerful, coiled posture from which action will

erupt.

Considering

the emotive hold the image has over the Zulu nation of 9 million people, it is

advisable to get the image correct. Our Zulus don’t take kindly to any slight

directed to their kingly lineage.

Constructive comments are welcome

ReplyDelete